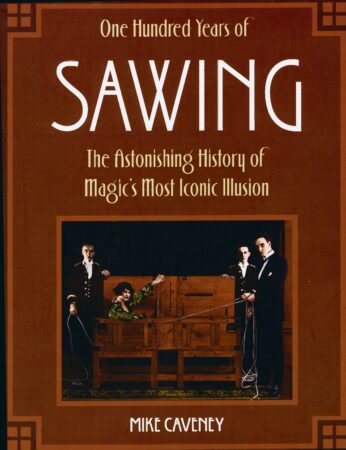

Description

Effect: After spending fifty years collecting Sawing in Half memorabilia, and the past year and a half researching and writing this incredible story, I couldn’t be more excited for you to see the finished product.

Learn how this trick became the most popular attraction in all of show business and then turned into a war that was waged on vaudeville and music hall stages around the world by many of the most famous names in magic. It is a tale of inspired originality, blatant thievery, backstage intrigue, unbridled egos and endless lawsuits. It is an illusion that has never stopped being reinvented and continues to baffle modern-day audiences. To coincide with the 100th anniversary of its first public performance, We are releasing this comprehensive history of Sawing a Woman in Half in the quality you have come to expect from Magic Words.

Contents:

Preface 13

Introduction 15

PART 1 – Before 1921 19

The Westcar Papyrus 19

The First Vertical Sawing 23

The Discoverie of Witchcraft 24

Robert-Houdin 26

Thomas Tobin and The Sphinx Illusion27

Palingenesia 28

The Hanlon Brothers 32

Professor Hengler 34

Charles De Vere 37

Percy Tibbles 42

P.T. Selbit 43

Vai Walker 44

Stanley Collins 45

Sawing Through a Woman 46

PART 2-1921 49

Horace Goldin 57

Harry Jansen 78

Servais Le Roy 81

Vaudeville85

The Great Leon 92

Preparations for War 100

P.T Selbit arrives in America 104

Cue the Lawyers 111

Mexican Hermann 113

Alexander Pantages 114

Burn Out120

PART 3-After 1921 129

Disaster Film 131

Carl Owen and The Man Who Knows141

Linden Heverly 148

Walter Gibson 151

Al Flosso 153

Jack Gwynne 154

Emil Jarrow 157

David Swift 158

Silent Mora 162

Charles Carter 164

Percy Abbott 175

Will Nicola 178

Cecil Barrie 180

Les Levante 183

Subduing a Woman with Bayonets 185

Dai Vernon 186

OKEH Records187

Tearing a Woman Apart 188

Charcot 193

Harry Jansen/Dante 195

Goldin vs. Dante 198

Goldin vs. Carter 209

The Buzz Saw Illusion226

Alpe Barbour 227

The Living Miracle 231

Harry Blackstone Sr. 241

Frank Luckner 244

Lester Lake 246

Carter the Great’s Buzz Saw Illusion 251

Joseph Dunninger 253

Dunninger’s Other Buzz Saw 258

The Great Lester 260

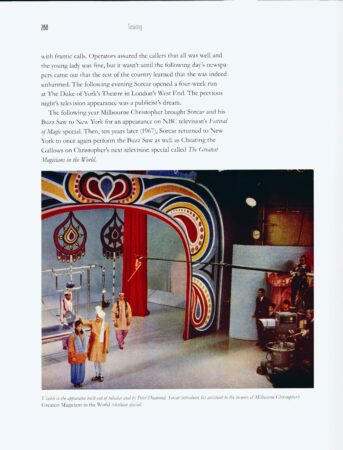

PC. Sorcar 265

The Orange Show 269

Joseph Ovette 271

The R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

Goldin vs. Dante – Rematch 281

Farewell P.T. Selbit 287

Anastasius Kasfikis 289

Guy Jarrett 292

George LaLonde297

David Bamberg 298

Rajah Raboid I Maurice Kitchen 302

Maurice Rooklyn 314

Cantarelli 316

Robert Harbin 318

Virgil Mulkey 323

Zati Sungur 328

Tihany 333

Robert “Torchy” Towner 333

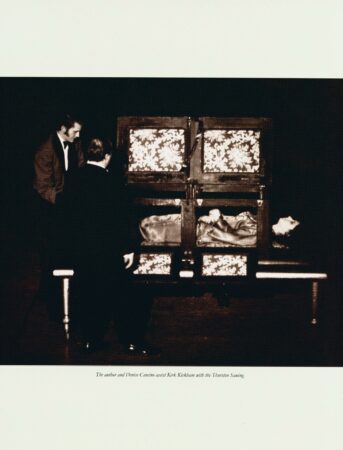

Kirk Kirkham 335

John Daniel 337

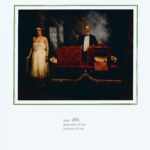

Virgil & Julie347

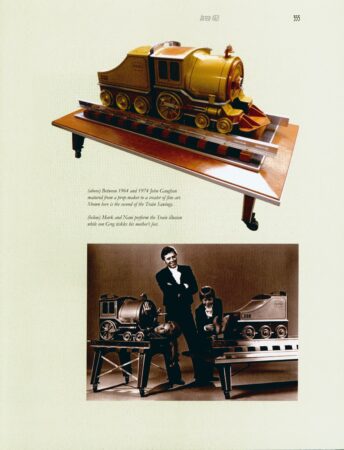

Mark Wilson 352

Richiardi J r. 356

Channing Pollock 368

Alan Wakeling 372

David Copperfield376

Crystal Sawing 390

Penn & Teller 394

Kevin James 396

Jim Steinmeyer 398

No End in Sight 401

Secrets Exposed 404

The End of the Road 412

Bibliography 419

Index 423

- #15 in our series of Magical Pro-Files

- 9 by 12 inches

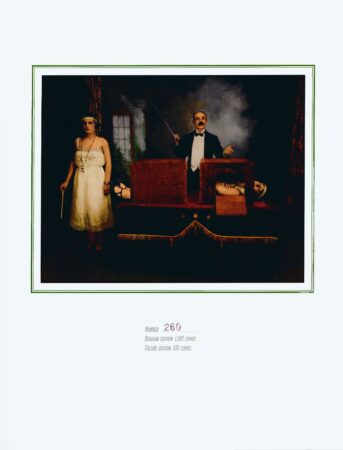

- 440 pages printed in full color on heavy art matte paper

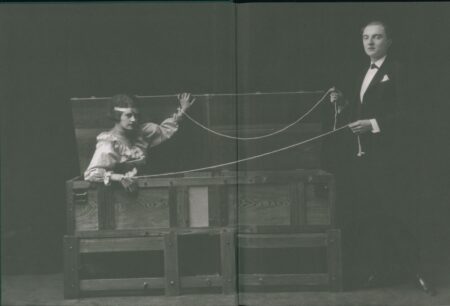

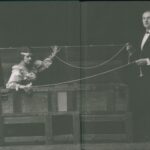

- 368 photographs

- Printed endsheets

- Full color dust jacket

- Published in 2021

Genii magazine review

Who knew that the world’s most famous stage illusion would also spawn magic’s biggest and most star-studded soap opera? Considering that he has spent the last 50 years of his life peeling back every layer of every truth (and the stretched versions thereof), Mike Caveney certainly knows better than most. In an expectedly pretty, vibrant photo-laden, hard-bound tome – the style of which the author is justly respected for – the reader embarks on an epic of torture, illusion, delusion, thievery, deceit, pandering, exposure, and lots of litigation.

While its title is One Hundred Years of Sawing, an astonishingly significant bulk of this historic narrative takes place in one year: 1921. Most every magician with a cursory knowledge of the trick’s history knows the names P.T. Selbit and Horace Goldin. They have an understanding or at least belief that Selbit first introduced the concept to the world but that Goldin was the initial magician to present it in the United States. From there, the amateur historians’ grasp of who did what, when, and where wants at varying rates. With every turn of the page, the onion layers that Caveney peel back give readers new surprises and alternative views on many of the 20th century “heroes” who laid the groundwork for the magic of today.

The Too-Long-Didn’t-Read version of this journey might quip that Selbit inspired an ugly ego war with a puzzle, Goldin was a lawsuit-happy and insecure whiner turned sell-out, the vaudevillian theater owners were essentially the mafia (without the killing?), and every magician in the 1920s was desperate for a taste of the action. The detailed realities that lead me to abbreviate them as such are as rich and fascinating as they are sad and ridiculous.

Caveney’s masterful storytelling captures our interest from the beginning with an anecdote of verbal cleverness that sets the tone for us to appreciate Goldin’s sly wording used to patent his stolen ideas. Another early story of a desperate David Copperfield fan insisting that the master illusionist should use his genuine magical powers to heal the man’s son serves as a healthy reminder that we magicians play with perceived power, and there are few such powers as venerable as the ability to conquer pain and death. “If a magician cuts a piece of rope in half and then doesn’t restore it, who cares?… But if a human being takes the place of the rope…”

The story launches back into history of human fascination with torture and truly horrific methods of execution the likes of which decidedly inspired daydreams of conjurors of the past. The author depicts a particularly interesting thought experiment that Robert-Houdin put forth as a story he claimed to witness: “Cutting a Man into Twins.” While the evidence leads us to believe that the depicted story never occurred and even still wasn’t truly the same as any version of sawing through a person we have come to know, it is curious that between this and other legends there wasn’t a genuine attempt to conquer the illusion until the 20th century. Yet this book and its comprehensive notations are thoroughly convincing in their veracity.

The lead up to the 1921 section of the book is a tightly woven series of after-the-fact claims by creators either suggesting to have had the idea first or questioning if there maybe were others who may have some version of “Sawing” pre-Selbit. Once we watch the humble curtain pulled back on the main show on a kitchen table in the U.K. and picture Selbit “Sawing Through a Woman,” we simultaneously stumble across perhaps the best line of the entire book, “For one month the world had no idea that P.T. Selbit was harboring a sleeping giant that when unleashed upon the world, would become a tsunami of bisected women.”

As enthralling as are all of the stories of lawsuits, envy, and lies between magicians over the book’s namesake, the author spends healthy and equally captivating verbiage on the history of the trick’s macabre inspirations and related history. The depiction of ancient execution techniques, the potentially history-changing disapproval of King James I over Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft, and Caveney’s talent for leading us along a bit before revealing the commonly known identity of certain iconic names (e.g., Harry Jansen becoming Dante) all make for a delightful read no matter what the reader’s pre-existing knowledge may be. One of the most informative and heart-wrenching sections of the book is his chapter on the history of vaudeville and the handful of wealthy controlling men who ruthlessly dictated who could perform what, where, and when in any of their tightly owned and operated theaters across the United States. These men set the rules, and woe to any hopeful performer who didn’t comply with them or the five percent commissions for all meager performance fees. All this to say nothing of the similar rackets in Black entertainers’ markets: the author makes it clear that the performers were in no way in control of how vaudeville went down. This part of the story gets extra messy and interesting) when Horace Goldin negotiates with the bookers to make sure that no one, including the trick’s rightful creator, could perform it but him. This, along with a head-spinning list of false and unreasonable claims, created more buckets of bad blood among magicians than those used in the publicity stunts to garner the attention of theater passersby.

The book makes it very hard to genuinely like any of its players, least of all Goldin. Caveney is fair and allows the plentiful letters, ads, and patent claims to speak for themselves, so much so that it’s hard not to be frustrated with Goldin’s hubris and back-stabbing capitalization as anything other than being bad for magic at the time. The entirety of the war this already accomplished magician waged on Selbit, and eventually on anyone who so much as uttered an interest in performing (not) his illusion, did shine the brightest spotlight on this trick such that it became the overwhelming talk of every publication, and not just the magic ones. The litigious, mudslinging war became extra fascinating when Selbit arrived in the States. The author’s detailed accounts of this unstoppable publicity machine reveal that neither Selbit nor Goldin could keep up with the public’s demand to see their respective spectacles. So much so that some of the most interesting anecdotes in the story revolve around the teams of performers each licensed to perform their creators’ tricks around the country until certainly no-one had not seen it, and probably multiple times.

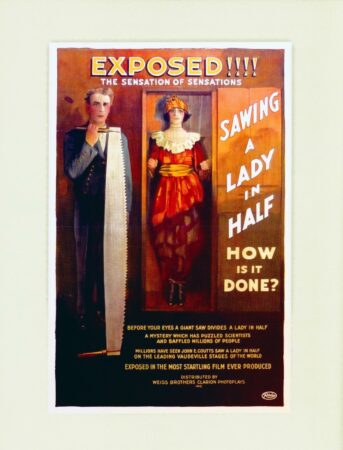

It is at this point when the soap opera gets dirtier; with the public fully sated by “bisected women” and with the advent of the moving picture, a whole new and horrifying problem came to life: widespread exposure. Filmmakers, “science” publications, unmasked magicians, and even ad campaigns capitalized on showing various ways in which women could be safely sawed in half, because as Camel cigarettes claimed in the 1930s, “It’s fun to be fooled… it’s more fun to know.”

The complexity of these exposure stories and their various other players – who stole what from whom, the depths to which Goldin would stoop to protect his name, who invented the buzz saw versions, and as important; who didn’t, all comprises a dizzying revelation of both the clever ingenuity but also the petty egotism of the giants on whose shoulders we stand today. And all because of a single trick.

The account thus far all takes place in just the first half of the book, but the story by no means slows down. As mentioned earlier, it is a veritable who’s who of “Hey! I invented that!” The author continues to clarify who did likely invent what, and who did or did not steal from whom. A bit of intrigue lies around Harry Blackstone, Sr., lifting certain effects from Goldin _ “Blown to Atoms,” a human vanish with a cannon, for example – but very cheaply purchasing the “Buzz Saw” illusion from one down-on-his-luck Lester Lake.

We learn of The Great Sorcar and a brilliant but horrifying BBC publicity stunt akin to the years of gory “Sawing” that Richiardi Jr. performed with real (animal) blood and intestines. Caveney recounts the brilliant and funny work with Johnny Eck and his “half-brother,” Robert, but also reveals stories of their vastly different personalities. And of course, we look to the more modern artistic ventures of Jim Steinmeyer. The book would not be complete without addressing the body-sawing renditions by John Daniel, Carl Owen, Alan Wakeling, Mark Wilson, Doug Henning, Kevin James, David Copperfield, and Penn & Teller. If there is a relatively well-known illusionist, One Hundred Years of Sawing probably at least makes mention of their almost certain association with the now legendary plot. It may cross some reader’s minds to ask if the various methods used to accomplish the illusion are discussed. While the basics from its very beginning are discussed, beautiful and often revelatory photographs fill the volume, and some of almost mocking exposure drawings adorn the pages, none of this is the point or anywhere as interesting as the story surrounding the subject matter.

As Richiardi would state following his visceral version of the trick, “Of course it’s a trick. But was it done well?” Of course, this is a written historical account, but it’s done well. One Hundred Years of Sawing is an elegant, thorough, captivating passion project that beautifully documents the wild, international history of one of the world’s most famous illusions.

Review by Frances Menotti